Curing Cancer for Social Networks: Solving the "Signal-to-Noise Ratio" Problem

Information, Consensus, and Human Networks

The most important communication tool of today is the modern social network. Every day, billions of people gather to share information in the blink of an eye. They changed the rules of media, politics, culture, and even technology itself. But from all of these advances, they have started to fail at the foundations of their communication models - the signal-to-noise ratio is bad and getting worse.

As the root cause, we are rediscovering what happens when we can’t “hear” each other. And since mass scale communication is from which we assemble our knowledge, decide the future, and maintain world peace, this might be the most important problem in the world.

When solved, we will speed up the evolution of humanity. The ability to coordinate information at mass scale will help us discover new ideas - hidden behind the archaic algorithms that prioritize the familiar, and obscure the unfamiliar. We will find groundbreaking secrets again. We will more easily source labor, capital, and resources for their best uses. We will reach consensus and get things right.

Historical Precedent

In every major step of communications technology, from cross-country telephone lines to undersea internet cables, we have championed the recurring problem of the signal-to-noise ratio. Although our lines and cables are more so digital today (connecting users to information), we can’t neglect our fundamentals. Currently, we have a complex challenge but our track record is perfect.

For social networks, we’ve had a harbinger of this problem before with Myspace. In 2005, it was sold to NewsCorp and they began to commercialize. The signal-to-noise ratio turned poor. Ads and brands took over your space and bots commented more than friends. We sought high social signal; so when an alternative called Facebook started to grow, we migrated. And rather than a new special feature, we moved there because we could “hear” our friends and local network (colleges) better. That, and the exclusivity factor.

Our social intelligence jumped. We got to learn about the people in our locale. As we knew more people we became closer and more trusting, which generated high-quality, reliable information at scale. The world was well-connected for what only seemed to be a moment - until the noise started to creep back. The pressure to “connect the world” was too great.

We all know the troubles of present day social media, but we must remember that it wasn’t always like this and there was a golden era. Today, history doesn’t repeat itself but it rhymes, and we have a more intricate problem with the velocity of our information, human network dynamics, and trust itself.

Understanding Information Velocity

In networks, there are many factors that shape how information flows through them. Below is an overview of the primary factors.

Connections

The amount of connections one has on social networks is the main measure of velocity. The more followers, the bigger the reach. This is simply understood when looking at a single account but when considering the amount of connections across a whole network, the average amount of connections, or that every connection is not equal, then we have a more complex scenario.

Degrees of Separation

You may have heard of “The Six Degrees of Separation” which is the idea that we are all within six or fewer social connections (friends of friends) of one another. This idea originated in 1929 and was popularized in 1990, but as of 2016 the average degree of separation of Facebook users is 3.57. Sure, information can jump globally faster but is faster always better? Can we be over-connected? What if we are breaking a key human function by reducing this separation to lower than natural limits? We’ll revisit these questions later.

Local Discovery & Global Discovery

‘Local’ used to only mean your neighborhood, town, or city. Today as we’re connected around the world, some people, content, and brands (sources of information) are digitally closer to us than others - this creates a locality. But our cities have failed at scaling trust and community, which pushed us further online in order to seek information and people like us. Now, local discovery can come from a flyer on your street as well as a group chat. Local no longer implies physical proximity.

Conversely, global discovery often happens in the form of global publication with public profiles and public content; usually delivered by feeds. As social media grew the jump from local to global became easy; but we lost significant agency to the algorithms. When discovering what is most relevant to us with limited time and interest - ideas, people, or events - we often mistake engagement for relevance. Today we all have the potential for global exposure. But if everyone does, how do we know what memes (discrete units of knowledge, gossip, jokes, etc.) are right for us?

Human (Social) Networks

Knowing that information is moving faster than ever, it’s important to understand that there are some innate social limitations with humans. Below we’ll cover which of those limitations are being breached as well as other concepts that shape our identity, community, and trust.

Our Social Limitations

While today we live in cities that have millions of people, our brains are still running on a 1,000+ year old “small town software”. There are three limitations to highlight:

Dunbar’s Number (150) is your brain’s limit of meaningful relationships; or the people you can really know. It has inner circles too - your top 5, 15, 50, and 150. Your 5 are your most intimate “call at 3am for a ride” type of friends. Your 15 are what psychologists call “your sympathy circle” that you spend about 60% of your time with. Your 50 are your friends; or those you might invite out to a big party for a birthday or celebration. Your 150 - as Professor Dunbar puts it - are the people who if you bumped into them at the pub, you wouldn’t mind sitting down and continuing conversation over your pint together.

2.5 Degrees Away: Researchers found that, within human-scale communities, information only travels about 2.5 degrees away until naturally dissipating - unless it was a highly viral piece of information like news of war or disease. Something interesting happens in this trust chain of “friends of friends of friends”: Consider me as your friend. I (1st degree) know a great restaurant. My friend (2nd degree) knows a great restaurant. My friend’s brother (3rd degree) knows a great restaurant. Most would agree that the recommendation’s strength greatly drops off between 2nd and 3rd degree.

Community of 7,000: Individuals have no effective voice in any community of more than 5000-10,000 persons - small enough to give the average person an immediate link to the most powerful people. This is an old idea. It was the model for Athenian democracy and it was the tack Confucius took in his book on government. There is great freedom in initiating action within a small community, but this is also a method for mitigating corruption. In fact Thomas Jefferson, in his plan for American democracy, wanted to spread out the power, not because “the people” were so bright and clever but precisely because they were prone to error.

Networks and Human Behavior

We are individuals and we are networks, but it’s possible to make a case that we are more so a network than an individual. We’ll cover a couple concepts to learn how our networks shape our behaviors and identity.

Mimetic Desire (think ‘mime’ or ‘mimicking’) is a theory by René Gerard that shines light on why we desire what we desire. In Gerard’s own words:

"Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires."

This also applies to how we (or the markets) derive value and why popular ideas (or trends) are so alluring. When Peter Thiel invested into Facebook in 2004, he saw it as a “mimetic machine” that would increase the rate of mimesis. He was right.

There is a sister concept to mimetics called homophily - colloquially known as “birds of a feather flock together”. Homophily lowers stress and helps us better coordinate our daily lives because we can predict the behaviors and reactions of people close to us. Instead of local geography defining our communities, we rely more on homophily and repeated contact to define our trusted circles of friends. These friends shape our beliefs, behaviors, and are from which we derive our influence.

Community Boundaries

As tribal animals that use inner circles to function, community boundaries are important in allowing us to coordinate and trust each other. Without these barriers (as in our cosmopolitan cities) it dampens all significant variety, arrests most of the possibilities for differentiation, and encourages conformity. This creates basic people - or liking likable things to be liked - and is the death of authenticity.

"Mass society not only creates a confusing situation in which people find it hard to find themselves - it also creates chaos, in which people are confronted by impossible variety - the variety becomes a slush, which then concentrates merely on the most obvious."

-Joseph Klapper, The Effects of Mass Communication

Our modern social networks function as our digital cities but growing forever without boundaries is not sustainable. We need a new model that gives us connectivity as well as space - as much as possible but no more - to facilitate our individual growth and then gradually expose ourselves to the rest of the world.

Christopher Alexander gives an idea what said model would look like:

“The metropolis must contain a large number of different subcultures, each one strongly articulated, with its own values sharply delineated, and sharply distinguished from the others. But though these subcultures must be sharp and distinct and separate, they must not be closed; they must be readily accessible to one another, so that a person can move easily from one to another, and can settle in the one which suits him best.”

Existing social media platforms have excellent utility with their high information velocity for global exposure. Group chats have an application for private small groups to speak with high signal and low noise. The model above could not be introduced to either without disrupting their utility; instead it’s likely it will emerge as a third, middle layer that facilitates communication between private networks at mass scale.

Trust

When we first meet someone we begin moving through the tenets of friendship:

Mutual knowledge - We learn about each other’s lives

Mutual favors - I buy you a beer, you buy me a beer

Mutual vulnerability - “I’m not sure about my future and I don’t know what to do.”

All of this is encompassed by a common story we tell ourselves about how we met, what we did, what we’re both interested in, etc.

Through repeated interactions, trust and reputation form on an individual scale, but what happens when you start to introduce friends? Trust then starts to form on a network scale, creating community. We give our friends of friends a degree of trust by extension - and it works generally well because as more people know each other there is greater risk of negative reputation/tribal exile and therefore less risk of abuse or mistreatment. Without community density, we move slowly to be safer.

Social media suffers a variety of trust problems: fake accounts, information overload with faulty sourcing, and no well-governing method for maintaining reputation in the “community”. On top of all this, there is abysmal bot pollution.

One could say social media functions better as an untrusted place. Assume nothing is true, scrutinize all interpretations of facts, get down to raw data only. This has a utility but we also need a trusted place to have careful deliberation and balance our decision making. Group chat interfaces are too slow for dissemination of information and too noisy to support hundreds or thousands of people’s voices. Again, there is space for a special middle layer that enables platform efficiency with a dense web of trust.

By now we’ve learned how we derive value, beliefs, behaviors, power, trends, trust, and our own desires from our networks. Moving into the raw forms of information (facts and consensus) we’ll learn how we translate them into knowledge and wisdom.

Achieving Social Accuracy

Answers are available in abundance, and are easy to find; sourcing from the internet, media, and our networks. We can learn falsehoods as well as facts, and we often confuse facts as consensus (an agreement on the interpretation of facts). Sometimes even popular consensus can be wrong. How do we mitigate this? How do we ensure the highest quality, reliable information is generated?

Facts & Consensus

Facts spread like a binary switch: 0 and 1. You know the fact or you don’t. You saw the meme or you didn’t. You know the secret or you don’t.

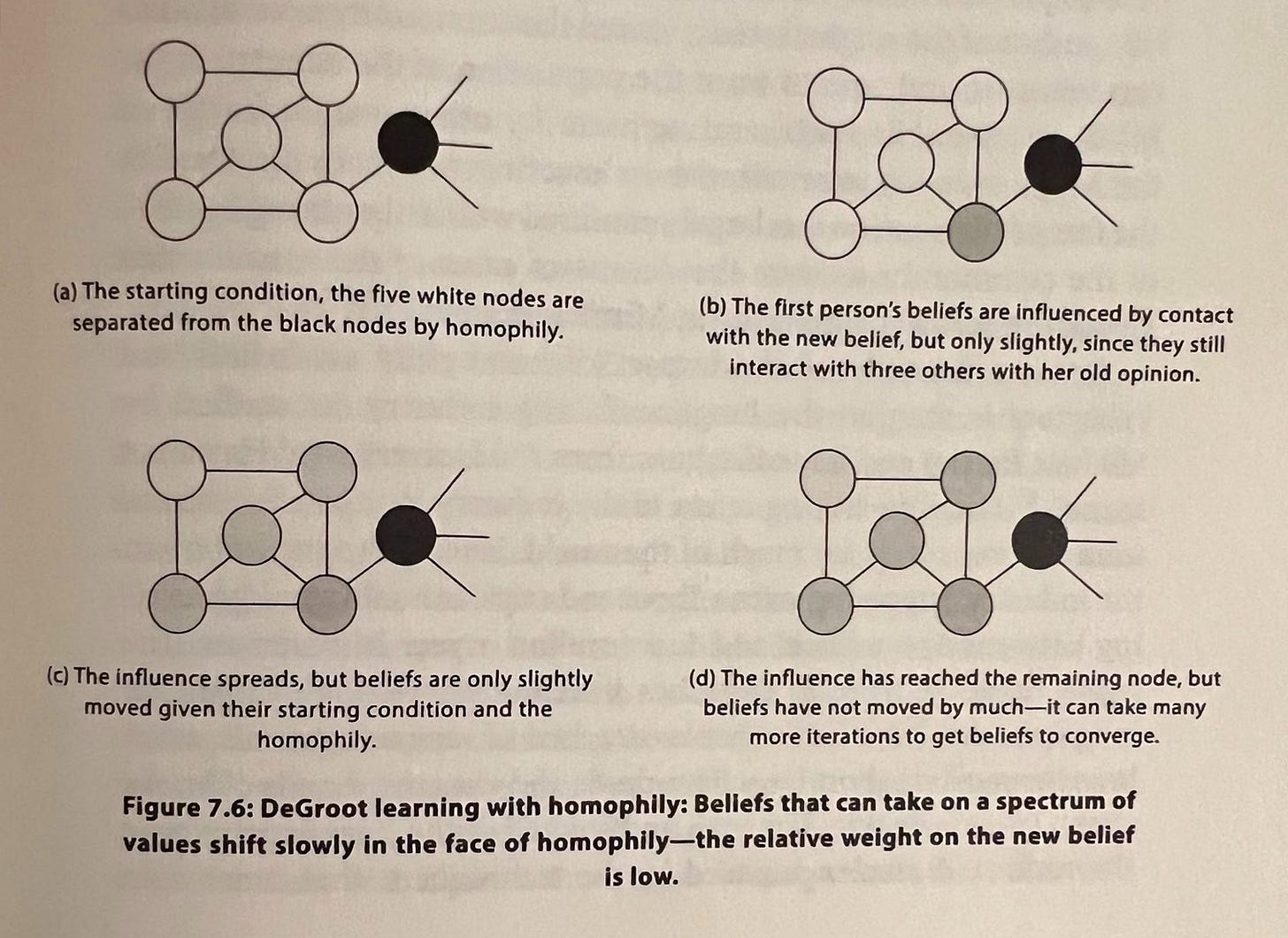

Consensus spreads across a network more like a spectrum: if faction #1’s idea is “yellow” and faction #2’s idea is “blue” (and they are equally represented), there is careful deliberation (without any preferences to manipulate each other’s beliefs), then the overall consensus will be “green”. Of course, it’s never this simple, but it’s much easier to achieve in smaller groups than larger ones. See the image below for reference.

As we learned, homophily clumps ideas together which make them more resilient to outside ideas - like a firewall, it acts as a community boundary. But too much of any good thing is bad, and so in extremes we see polarization like at the extents of the Overton Window. Applying consensus, you can understand the incentive to exaggerate beliefs in order to influence others.

An essential task of any organization is processing and aggregating information from multiple sources - both internal and external. Eventually, knowledge emerges from a rich storage, and only then wisdom can be extracted to gain insight, understanding, and acceptance of fundamental nature.

Ensure the following while deliberating for highest quality outcomes:

Diversity of views and experiences that produces a range of opinions to learn from.

Experiences and viewpoints cannot be biased in any systemic way.

Various views have to be aggregated; instead of picking the average or median.

Google’s thesis says “primary sources generate high-quality, reliable information at scale.” In normal social environments, primary sources are a synonym for trust or reputation; but since social media systems don’t mimic these trusted environments, the utility of reputation breaks. The inequality of influence - and noise from an unknown crowd - further impedes deliberation; so we can understand why they do not produce (nor sort for) high-quality, reliable information at scale.

Storytelling

One of the main evolutionary features of humans that sets us apart from other animals is our ability to communicate abstract ideas, across generations, without you having to personally experience it to know it. Before writing, we just had storytelling.

In 388 B.C. Plato urged the city fathers of Athens to exile all storytellers and poets. He argued they are a threat to society because they deal with ideas covertly - not in the open, rational manner of philosophers. Instead, they conceal their ideas inside the seductive emotions of art. Every effective story sends out a charged idea, in effect compelling the idea into us, so that we must believe. In fact, the persuasive power of a story is so great that we may believe its meaning even if we find it morally repellent.

Our ability to communicate in the abstract makes us susceptible to deception and enables errors. Next time you’re hearing some news from a friend or legacy media, pay attention to when they are listing facts and when they switch into storytelling. As dangerous as this tool might be, sometimes its “necessary” to inspire the troops, to calm the crowd, or to convince an employer to offer you a position. Heck, the entire industry of advertising is based on telling stories. We can tell a story to a friend or small community, but it’s a whole other manner to conduct storytelling at mass scale - it’s a great power separated from its great responsibility.

No civilization, including Plato’s, has ever been destroyed because its citizens learned too much truth - the same cannot be said for one gripped by a compelling story.

By going on social media, much like walking out in Times Square, we give our consent to be storytold - or advertised to - and unfortunately we’re losing more agency by the day. In the noise of social and legacy media, simple facts don’t work anymore; only stories stand out with their emotionally charged ideas. Herein lies a singular reason to regulate (not by law, but personal intent) the stories thrust upon us. The next major platform should respect this.

The Wisdom and Folly of the Crowd

When we cannot answer a question based on our own personal experience, and we have only anecdotes at best, we must rely on what we have heard from others and “trusted sources”. This allows the dramatic and persistent division that we see in people’s beliefs on questions of fact and it leaves us open to doubts, superstition, and polarization. But it also enables people to achieve great humanistic advances, as in the case of going to the moon where the average engineer only knew of their own specialty while being ignorant of others.

Mass movements can bring enormous change for better or for worse. Some arise organically, but far more arise inorganically when a person or group takes advantage of the right social conditions to induce a catalyst. With the rise of mass media, the rules have changed and now the there are countless other ways of influencing the masses - even going as far to produce the social preconditions. With just a few coordinated influencers, or a news organization getting ahead of the story, the public is successfully propagandized with ease.

People are prone to wishful thinking. They can believe an assertion and espouse it as truth in the face of overwhelming evidence and facts to contrary, simply because they wish that things were so. Also, people are generally gullible, easily mislead, and conformist - as in the Asch Conformity Experiments. Fortunately, the higher the stakes, the more incentivized people are to actively seek and filter information, rather than let opinions come to them. Unfortunately, social media has trained us to be “fed” information and ideas rather than considering first and intentionally searching after - this is contrary to human nature.

We must regain our consent to outside influences. Modern social platforms have naively given priority to global brands and organizations to nestle information and ideas amongst our most personal interactions with our friends. As we are emotionally open - and willing to receive - with our friends, close on the heels of their content is a charged idea or story from a stranger.

If we want to see the potential of our collective wisdom in the 21st century, we need to reconnect our social networks in a human way. Accept the limits of our nature. Give people space away from outside influences. Trust that a dense community can produce uncommon ideas that end up being breakthroughs. It all starts with belief.

The Contrarian Solution

Most social networks don’t have the problem with noise innately, it just a matter of breaking at scale. You may have heard of the quote, “Imagine a being who is all powerful, all knowing, and is everywhere. What does such a being lack? Limitation.” Social media knows only one mode of operation: grow forever.

Sorting algorithms emerged out of necessity to filter big data. With no limitation to their global discovery protocol and an addiction to engagement, the algorithms will forever be imprecise and can only be efficient at sourcing popularly relevant content. This relates to the dilution of community boundaries and therefore the reduction of all lifestyles to a common denominator.

What if we didn’t have big data? In local discovery information models where there is an inherent limitation, it’s less backend infrastructure like algorithms that control and shape how knowledge flows; and more so the human-facing user interfaces.

3 Types of User Interfaces (UI) & Their Effects

There is enormous complexity in the effects of UIs. The most important element in terms of the signal and noise is their information flows; so this is where we will exclusively focus.

Boost Model - Twitter

You’ll notice that most decentralized social networks copy this UI model; that’s because the Boost Model allows information to travel more quickly than any other. You can have unlimited connections, retweets/boosts make it easy to pass information through the degrees of separation, and there’s even a global trending list that connects the most isolated users to popular content. It is relatively easy network type to get started with large influencers that operate as gravity centers for the network. Out of all other models, the Boost Model has changed the least since its inception, alluding to its longevity potential and utility.

Subcategories Model - Reddit

Rather than users being the destinations for content, the Subcategories Model (or Subreddits) allow users to create a space that they control the information flows of. This has the benefit of high signal and low noise generally when these spaces are small; but as they grow bigger and more discoverable by the network, their influence attracts bad actors, sometimes faulty moderation (censorship), and a weakening of their space’s identity. Although this model seems federated, a small amount of moderators tend to control most of the largest spaces; and without any limitation to their authority, it makes this model susceptible to group think via manufactured consent.

Private Feed Model - Early Facebook

In this model, information moves the slowest compared to the others. Private networks generally have less connections, resulting in a higher average degree of separation, and a local discovery only within their network. Like the early days of Facebook, these work great in the beginning but eventually grow too noisy after a point of diminishing returns. This requires the algorithm to take more agency in sorting content, in order to maintain relevance. Without any cap or limitation the benefits cannot scale. Facebook knew this, and bet on a global platform primed for engagement alone. Groups were the platform’s greatest increase of information velocity, shrinkage of degrees of separation, and dilution of community boundaries.

A Social Network Made For Humans

Social media is not simply bad - it has a purpose and utility - but it is not for our personal relationships or our local network to communicate through. It should be freed from the burden of our personal data so it can flourish into the best global brand and audience space it can be. Like the mall, we would hang out with our friends there sometimes; and then go home.

People tend to only look at one problem at a time, or ask the wrong question. Instead of an idea based on destroying the past, we would profess an idea about building the future is far more useful. What is required of a social network to facilitate human nature? How do we maintain both social intelligence and a high signal-to-noise ratio at scale? How do we protect individual sovereignty while also enabling the potential of a community?

We begin with Dunbar’s Number by limiting everyone to 150 connections to preserve quality of people, relevance, and trust. By only connecting to friends of friends, we maintain a sustainable Degree of Separation and private Local Discovery. There are no public profiles nor public content. This generally limits Community Size to 5,000-10,000 where the average person has more effective reach (signal) than on social media; and get connected to far more popular and powerful people in their network.

Since there are no influencers, algorithms sorting big data, or sponsored thought (ads), Homophily & Memetics are allowed to provide their benefits and also have their risks mitigated as there is now protection from outside influences. Limitation of size and discovery alleviates noise and creates Community Boundaries so that we can explore our identities fully and freely - coloring the network in a vast diversity of lifestyles. Closeness builds Trust, yielding faster information through a local network with high social intelligence.

Each person has total control of their environment; and can now be given agency over what shapes their beliefs and behaviors. When communities are given the task of Finding Consensus or Assembling Knowledge & Wisdom they can deliberate in solitude, taking time to repeatedly consider without global manipulation or bias. Uncommon, locally-relevant, and potentially genius ideas will breathe again.

The best UI for this case will combine the Private Feed Model and Subcategories Model. The “end user” gets a distinctly personal space to be with their friends - and also a way of broadcasting, around the world, to a local network of thousands of friends of friends. This is the most connected humans can be prior to diminishing returns of noise.

The Frontier Ahead

We were born too late to explore the world, too early to explore the cosmos, but born just at the right time to explore the human psyche - that is our frontier. (Funny enough, the recent advances in AI are now showing us a mirror, as we evaluate ourselves and question why.) Humans are seekers of the great beyond. We are pioneers. The world needs crazy contrarian ideas to breakthrough this trough of incremental improvements; but this implies taking a risk on potentially hazardous paths. Vulnerability is power.

This social network may play a role in how we aggregate our new uncommon knowledge; as it begins to percolate from our small local networks, gradually spreading around the world. Its highest purpose is facilitation of the community and preservation of the individual. Knowing this won’t be without resistance from the old world, to those who wish to work with us in the coming years should remember the Shackleton Expedition Ad:

WANTED: MEN FOR HAZARDOUS JOURNEY. SMALL WAGES, BITTER COLD, LONG MONTHS OF COMPLETE DARKNESS, CONSTANT DANGER, SAFE RETURN DOUBTFUL. HONOR AND RECOGNITION IN CASE OF SUCCESS.

If our message resonates with you, we call for your aid. Join us. Please contact hello@150.earth for job and investment opportunities. Here’s to the future.

Still curious? Download the iOS app here.

Recommended Reading

I used these books (and copied some passages within them) to find an understanding of human social dynamics and their place in social networks. I highly recommend them and cannot commend the authors enough.

A Pattern Language - Christopher Alexander

The Human Network - Matthew O. Jackson

What Technology Wants - Kevin Kelly

The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation - Jon Gertner

The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements - Eric Hoffer

Propaganda - Edward Bernays

Story - Robert McKee

Happy Birthday! Our gym chats have been insightful and much appreciated 😊

- Christina "Sassy"

Hey Alex, read this again more slowly. I’m overwhelmingly positive on this and scratching my head a bit on where we disagree.

On the general and specific shapes of the problem you and I are pretty much wholly aligned. You can find old posts on my substack where I’ve been yammering on forever. I say that only as social proof of my sincerity and genuine care for the problem.

We live in a sea of attention epilepsy and unless you are willing to generate super loud l, and to most people, antisocial signals like political extremism you have trouble forming any kind of effective group. Antisocial behavior being a positive signal to other antisocial people.

My question for you, and the bit I started with in my own thinking, after you form groups how do you stitch them back together where they remain distinct but also can cooperate at that level to make some kind of meta group consensus?

Is this step one of a longer plan?

Will respond to your comment of my work on X.